I must confess, I have a special place in my heart for big stats. Not for the reasons most researchers will give – I don’t think the TRUTH lies within big numbers. No. But, I think massive amounts of data can give us two dimension of a story – sort of the breadth and width of things. And, in this case, the THING I am looking at today are picturebooks. To be precise – I’m looking at Great #OwnVoices Picturebooks.

The Cooperative Children’s Book Center is the children’s literature go to organization for Big Data. Publishers both big and small send books to the CBCC all year and the librarians (both staff and students) count all the things. The annual collection consists of “books typically available for sale to public schools and public libraries”.

As you can see, with a few exceptions (2004-05, 2013) there has been a steady increase in the number of children’s books published in the United States of America.

Too many publishers, scholars, authors, editors, librarians, and teachers have told us – People of Color, Native Americans, the LGBTQ community, people with disabilities, and non-neurotypical people – to wait our turn. We’ve been told that change takes times, and above all else, to give authors, editors, and publishers the benefit of the doubt. It stands to reason, if we wait for the market to grown, then the pie gets bigger, and the bigger the pie, the more share I get. Right? Right!?! RIGHT!?!?!?!?

Well, the results from the CCBC 2017 count is in and it is a freakin’ crime (thanks to Lee and Low for putting tother this infographic). I want to draw people attention to this bit, down here, near the bottom of the image …. you see that?

7%.

Seven. Siete. Sept. S-E-V-E-N. As in the 7 Deadly Sins kind of seven.

I’m not giving up and I know my colleagues are committed to educating literary gatekeepers to recognize the need for a rich variety of diverse #OwnVoices literature in classrooms and libraries. In addition, the authors aren’t stopping anytime soon. Providing children and young adults with a wide array of authentic representation is a change that will make us a better society – full stop.

Unfortunately, White writers and editors are freakin out about SEVEN PERCEPT! of children’s books that are published being by and about under represented communities. They are clutching pearls, and asking to see all the managers, because they are threatened by the very idea that we are demanding a wide array of representation written by the people being represented. Please see Nora Baskin’s Ted X talk for the best of this not-isolated-at-all-flaming-trash-heap of White fragility in action.

Instead of understanding #OwnVoices they decided White authors should write random non-White, non-straight, disabled, non-neurotypical characters, as long as those characters are just like them. You know, “normal”, which is White code for “White, like me.”

Instead of leaving you with this dismal state of affairs, I want to highlight some #OwnVoices picturebooks that you need for your library and classroom. In addition, I am going to URGE you to go to Goodreads and Amazon to post reviews!

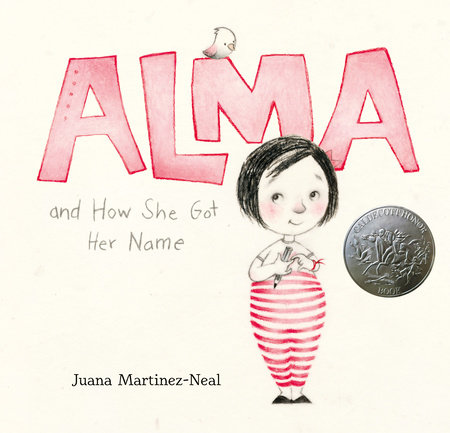

This picturebook just made me feel good about being Latina. Alma is a little girl with a big name – Alma Sofia Esperanza José Pura Candela. This book is a beautiful and loving illustration of the ways Latinx names recognize and honor our histories.

The illustrations by Martinez-Neal are striking in their quiet grace. Using what looks like pencil and charcoal Martinez-Neal brings a vibrancy to the lives of Alma’s ancestors, as well as to the ways she identifies and connects with them.

When We Were Alone by David Robertson and Julie Flett.

When We Were Alone by David Robertson and Julie Flett.

I used this book with my children’s literature classes because of the complex and subtle narrative structure. This book gave me, a non-indigenous person, a small glimpse of the fallout from the cultural genocide boarding schools perpetrated on Native Americans and First Nations people. (And yes, it was genocide. Calling it anything else and you are just trying to make yourself feel better).

The book features a young girl hanging out with her Kókom (grandmother) and asking her why does things like grow flowers, wear a long braid, and laugh with her brother. The reasons are all bound to her Kókom’s time in boarding school. Throughout the picturebook there are tensions: the simple premise and the hard subject matter; the plain faces and the expressiveness of those faces; the colorful beauty of the little girl and her Kókom alongside the drab and faded look to the boarding school images. Flett’s illustrations could be used as a master class in mood – a notoriously difficult literary concept to teach across k-12 English Language Arts classrooms. The changes in color palette from the present to the past signals the changes in time, place, and mood to the reader.

A Different Pond by Bao Phi and Thi Bui

Phi’s intimate story of an early morning fishing trip with his father is told in sparse text and rich colors. The gentle ways the story unfolds keeps many readers engaged and enthralled.

The deep melancholy of the book makes it stand out among children’s book. A tired young boy and his father getting up before day break to fish is familiar story. What makes A Different Pond unique is that it takes a common story and tells it from an immigrant’s point of view. The boy references his father’s accent (Vietnamese) “A kid at my school said my dad’s English sounds like a thick, dirty river.” The father tells the baitman, who he obviously knows well, that he’s got a second job. What surprises many readers is that this family is fishing not for sport, or fun but for sustenance. They talk about how difficult immigrating to the United States has been and why it is worth it for their family. And, by taking the young Bao Phi with him, this father is including him in his love and care for the family.

Reblogged this on debraj11.

Another excellent, thought provoking post. I think however, that in looking at the change in the number of books published you can’t look at the number of books received by the CCBC because that only indicates a change in the number of books they’ve received. I think we have to look at Library Book and Trade Almanac formerly the Bowker Annual to get the number of books published annual. Recently, they’ve parsed YA from the youth total

2015: 4,416 and 2016: 4,882

Childrens books

2015: 4,416

2016: 4,882

These numbers, however include everything from picture books, nonfic, comics… and not just the fiction we’re use to including. I do argue that even though we have to be more diligent to include IPOC authors in those various genres, the numbers of authors isn’t going to increase proportional the volume of books between the CCBC total and Bowker’s.

good point! I love librarians.