I know 2020 is lasting way longer than seems humanly possible. It is somehow august when it should clearly be 2025 with flying cars, genetically modified cats that bark, and small batch sour dough on tap. But, no. We are still in 2020 with all the things that are going horrendously wrong every single day.

But …

Jerry Craft won all the things for his graphic novel New Kid (https://jerrycraft.com/), including the 2020 Newbery Award. This is the first graphic novel to be awarded a Newbery, so now it the book can proudly wear a bright gold sticker declaring the book’s awesomeness. (I have mixed feelings about book awards so don’t expect me to figure the myriad of internal conflicts anytime soon.)

Jerry Craft won all the things for his graphic novel New Kid (https://jerrycraft.com/), including the 2020 Newbery Award. This is the first graphic novel to be awarded a Newbery, so now it the book can proudly wear a bright gold sticker declaring the book’s awesomeness. (I have mixed feelings about book awards so don’t expect me to figure the myriad of internal conflicts anytime soon.)

The book opens in a 2-page spread, with a boy free-falling through space, as he is being drawn into existence by an unseen hand. There is a set of text boxes that instantly break the 4th wall as the narrator, a 12 year old light skinned Black boy, who directly addresses the reader. We are told that he’s a comic book fan, he’s well educated, and he’s scared. There is a sketchbook with “Chapter 1 THE WAR OF ART”, as well as a few sketches falling off the page. Craft provides an opening that acts as a visual overture with everything laid out for the careful reader. I have to admit, I missed 90% of it all and had to return over and over to pick things out. It became a “Where’s Waldo” for both characters and events.

I can’t say enough positive things about this book. The story is a simple one – Black kid leaves his local school for a predominantly White, hugely privileged and pretty damn racist private school. He has to find his way, find his people, and learn how to navigate the physical space, the kids, and the teachers. The one thing he is never in doubt about is his own identity. I read New Kid a few months ago and loved it. Craft hits a balance between showing us a Black 12 year old and his world, and providing a greater commentary on race, class, expectations, exceptionalism and the ways we see and don’t see ourselves and each other.

I can’t say enough positive things about this book. The story is a simple one – Black kid leaves his local school for a predominantly White, hugely privileged and pretty damn racist private school. He has to find his way, find his people, and learn how to navigate the physical space, the kids, and the teachers. The one thing he is never in doubt about is his own identity. I read New Kid a few months ago and loved it. Craft hits a balance between showing us a Black 12 year old and his world, and providing a greater commentary on race, class, expectations, exceptionalism and the ways we see and don’t see ourselves and each other.

Craft provides enough visual details that lend a real world feel to the school. The halls and classrooms are populated with different kids – some identifiable and some that blend into the background. The representation of girls is a bit sparse until the end of the book but his take on the classic White woman liberal teacher is brilliant.

One thing I notices is that characters all LOOK different. This sometimes seems like such an obvious thing and small matter to a graphic novel. I mean, why would’t people look different? But, this is an aspect of #OwnVoice visual imagery that we do not pay enough attention to and this is an aspect that Craft comes back to over and over again. Black people of all shades, shapes, hair styles are abundant in the pages. But, perhaps it should bot be surprising, but there are also a number of Asian, Latinx and White people that are easily discernible across the book.

This is a group of kids I wanted to spend more time with, to see how the connected and disconnected with each other. Also, there are some of the best liberal White teacher rhetoric I have ever seen in a book – truly cringe inducing.

Go get this book.

Or read the next review and get both!

Green Lantern: Legacy by Minh Lê and Andie Tong does not have a big, shiny gold sticker but that doesn’t mean it is not a totally kick-butt comic.

I’m not a huge fan of Super hero comics. I am trying to get better about reading them, but I have to admit I tend to find them … lacking. Often, they assume or require an enormous amount of detailed background knowledge in order to understand the story. That’s why I tend to read origin stories – they don’t hold the bright and shiny assumption that I know what happened to Enid when Clive drove off in that white Mustang with the Florida plates. Because I do not know. The ugly truth is, I am not a good comic book reader.

I am also not a green lantern fan. I only know the basic outline …. ring + imagination = superpower to create anything. Fine.

But, I was excited to see this origin story BECAUSE I love Minh Le’s work (which you can find here) and you can get from your local library or any Black owned and independent book store. I shared Drawn Together with a class of second graders and it spawned lots of excitement and provided an important mentor text for their own inter-generational stories.

Green Lantern Legacy is the story of Tai Pham, a 13 year old who loves to draw, hang out with his two best friends, and happens to be the grandson of Kim Tran. Kim Tran was a Vietnamese immigrant and Green lantern.

As her grandson, Tai is not only the youngest lantern but he is also a generational choice – which seems like a big deal that I do not fully understand (please see my “bad at comic books” confession).

![Artwork] Tai Pham (Green Lantern: Legacy) pinup (by Andie Tong ...](https://booktoss.files.wordpress.com/2020/08/image.jpeg?w=181)

I truly appreciated Kim Tran’s general bad-assery in this book. She’s a loving grandma, a protector, and she owns a store that is an important resource for the neighborhood. I also appreciate seeing a woman who has a fully lived life represented in a comic. We see her as a young woman full of power who is ready to fight for her people. We also see her as an old woman, still ready to fight but also realizing she is at the end of her time.

The importance of telling an inter-generational tale shouldn’t be overlooked. The idealized nuclear family is incredibly over represented in children’s and YA literature so this purposeful and culturally sensible departure is terrific. Don’t underestimate Tai’s family representation as an important part of not only his story, but also Kim Tran’s story.

There is a bad guy, training montage, family tension and secret identities at play in this great origin story. Please make this as popular as it deserves to be – which is wildly so.

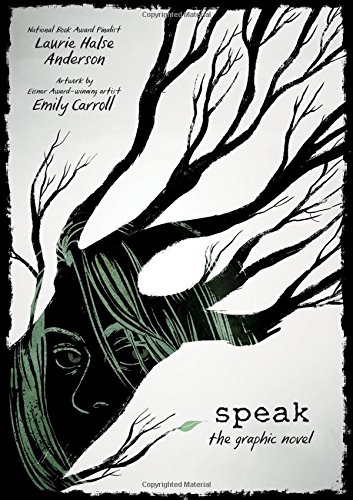

Full disclosure. I have met Laurie Halse Anderson a handful of times in professional settings and we follow each other on Twitter. I have never shared a meal, so she is not a friend, but I also would’t ignore her if I saw her at an airport. So, a professional acquaintance.

Full disclosure. I have met Laurie Halse Anderson a handful of times in professional settings and we follow each other on Twitter. I have never shared a meal, so she is not a friend, but I also would’t ignore her if I saw her at an airport. So, a professional acquaintance.

be honest, it looks promising. The cover is a study of blues. There is what looks like a human heart in the center, with two young women facing each other, touching foreheads, in an embrace. The young women are flanked by much more violent images that make up a slightly recessed background and are colored in a darker blue. On the left, three people are holding long knives and looking determined, above their heads are hands grasping something between thumb and for-finger. On the other side, there are people in riot gear, attack dogs, and a young man getting arrested.

be honest, it looks promising. The cover is a study of blues. There is what looks like a human heart in the center, with two young women facing each other, touching foreheads, in an embrace. The young women are flanked by much more violent images that make up a slightly recessed background and are colored in a darker blue. On the left, three people are holding long knives and looking determined, above their heads are hands grasping something between thumb and for-finger. On the other side, there are people in riot gear, attack dogs, and a young man getting arrested.

Book to Toss:

Book to Toss: Novgorodoff’s characters are drawn as caricatures of people but even given this more abstract and absurdist style she relies on some tried and true racist and sexist tropes.

Novgorodoff’s characters are drawn as caricatures of people but even given this more abstract and absurdist style she relies on some tried and true racist and sexist tropes.

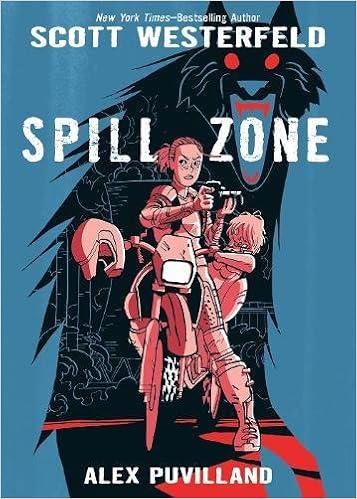

with this idea of creepy-ish and toughness existing simultaneously. Creepy elements include the red-eyed wolf with it’s open maw hovering behind the girl, as if it will chase her at any moment. The malevolent intent of the wolf seems clear and barely contained. The small but highly saturated areas of red – the wolf’s eyes, mouth, as well as what appears to be the spill in the bottom quarter of the cover – frame the image of the girl on the motocross bike.

with this idea of creepy-ish and toughness existing simultaneously. Creepy elements include the red-eyed wolf with it’s open maw hovering behind the girl, as if it will chase her at any moment. The malevolent intent of the wolf seems clear and barely contained. The small but highly saturated areas of red – the wolf’s eyes, mouth, as well as what appears to be the spill in the bottom quarter of the cover – frame the image of the girl on the motocross bike.

I don’t think of myself as a sentimental reader although there is a good chance that I am. I am always more clear about other people’s motives than I am about my own. I can clearly see when my friend is making a HUGE mistake or when my kids are being so prideful that it is going to come back and bite them in the butt. That kind of clarity is nearly impossible for me to glean from my own psyche.

I don’t think of myself as a sentimental reader although there is a good chance that I am. I am always more clear about other people’s motives than I am about my own. I can clearly see when my friend is making a HUGE mistake or when my kids are being so prideful that it is going to come back and bite them in the butt. That kind of clarity is nearly impossible for me to glean from my own psyche.