In research we often provide what is referred to as a positionality statement. It helps our readers understand who we are, how our experiences and identities effect our understandings of the subject we are writing about. Positionality statements help avoid the fiction that research is neutral. In the age of #OwnVoices I have come to realize, or maybe I have come to admit to the realization, that I believe an author’s identity, community, and experiences informs the work they produce.

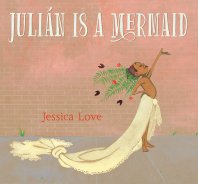

Librarian Angie Manfredi (@misskubelik ), Tweeted out about a book she wasn’t crazy about. Here is a link to the entire thread. “Our library copy of JULIAN IS A MERMAID has finally arrived and it is adorable but I NEED everyone in #kidlit to acknowledge it would NOT be getting this amount of love and attention if it were written by a gender non-conforming queer IPOC – it might not even have been published.” The book was written and illustrated by Jessica Love, a White, cis, woman.

For a long time I hesitated to write about Julián, a picturebook is about a boy who dreams of being a mermaid, transforms himself, and his abuela who upon seeing him dressed in a headpiece and flowing train, takes him to what I can only describe as a drag parade (the mermaid parade in Coney Island *1). The book and the author are being talked about, and will most likely win many book awards.

I did what I usually do when I’m wresting with a book that features identities or communities or content that I am unfamiliar with. I asked people I trust. I shared my thinking with them, and I listened. In many ways this essay is more about the conversations I had and continue to have while trying to come to terms, rather than some sort of clean conclusion. *I will be adding footnoted changes to this post as they happen.

When I first read the book I thought it was beautifully drawn. Full of soft colors, and gentle edges. Like fine pastels rubbed into expensive paper. There is a lushness to the images. When reading it I saw the care of the illustrator for her art, but I also so her Whiteness, her straightness, her cis-ness. I felt it in my bones and I could not shake the fact that I did not like the book. It was like eating a big meringue – sweet, technically beautiful, but it left a cloying, unpleasant taste. I wanted to name the taste, to objectify it, to explain it, to defend my dislike. I didn’t want to simply say “It isn’t an #OwnVoices book”. That was a convenient reason but not a complete one.

Literacy is a social act, and I find that my reading of the world is better when done in collaboration with others who do not share my view of the world, my history, or my identity. So, I talked to teachers who are Dominican, to librarians, and finally, to a trans girl named Indigo.

Stacey (not a pseudonym) is a teacher and she’s Dominican. I asked her about the book because I knew I needed to get handle on the language used. There are differences in the ways Latinxs speak and act within our communities and I didn’t want my Mexican-ness to over-ride the Dominican-ness that the White author was trying to capture. Stacey’s response was helpful. At first I asked about the physical features of the women, their dress, the ways they moved, and the shoes they wore. “I found that the story depicted Afro-Carribean culture pretty well. From the shape of the abuelita, her head scarfs and dress, to the figures of the other characters, I didn’t see anything problematic.”

Stacey was generous, and she shared an unprompted idea with me.

I may of completely misinterpreted the theme, but I don’t know how likely it is for a Caribbean grandma to to take her grandson to a drag show and give him pearls after catching him in drag the first time. I think this story minimizes the real struggle LBGTQ members face in Caribbean culture where many of them are not accepted by society as they are in America.

The ease in which Julián’s abuela accepts and encourages him to show his whole self might be something the author put into the book as a wish or hope. But, by creating this almost immediate acceptance, Jessica Love negated the real struggle so many Latinx LGBTQ people must go through. Is that is the message the author is trying to send? Probably. But, it lands flat to me. For me, this comes from a place of privilege that would rather a mermaid trope carry the message and ignore the very real issues at work.

Which lead me to a completely different Stacy and her colleague who helped me think about the whole mermaid deal. Stacy Collins (@darkliterata), who can be found over on the blog Medal on My Mind. I had lots of questions about the book.

Was this some sort of Trans Tail (Get it? Tale … like a story? and Tail like a mermaid? Sorry, I had no choice, the pun had to be written. I don’t make the rules). I get that there is a transformative narrative to mermaids, but if we are looking at a picturebook about a trans girl, or a gender fluid child, then why is Julián gendered on the very first page as male? Public librarian and friend Kazia Berkley-Cramer (@cateyekazia) pointed out the gendering thing and the fact that it continues throughout the book, even when he puts on a fancy headpiece, tablecloth tail, and big bauble-pearls his abuela hands over to complete his ensemble. She also wanted me to know that families are finding this book helpful and that isn’t nothing. But, for me, I keep looking at this book and I don’t think it is about a trans girl, or a gender fluid kid. It is really about a boy dressing up as a mermaid. Stacy Collins very aptly pointed out, “A fish tail is not inherently feminine, unless Julián wants it to be.”

It is important to point out (which I neglected to the first time this was posted) that Kazia was, overall, an advocate for the book. Her reasons were simple and compelling – her patrons. In her library she keeps the book in the “myself” section and Julián is a Mermaid provides her patrons with a character that they can watch come into being as without being chastised. In the first posting of this piece I neglected to give Kazia’s point a view much air. Probably because it departs from my own, but the fact is, there is a scarcity of books that show any kind of gender fluidity or flexibility with gender roles without punishment. That is a huge concern and, in that case, this book can do good things. (*4)

And, that is an issue I keep running into with this book. It isn’t clear what, if anything, Julián wants to express because this isn’t really Julián’s story. It is Jessica Love’s story, a story of a young Dominican boy, playing dress up or constructing himslelf, as imagined by a White, cis woman who brings her identity to the work, and with her identity comes her outsider’s gaze.

And, I think that is what bothers me the most. It isn’t JUST that Jessica Love isn’t a trans person of color. It is that there is no where in the book where I am not aware that this is another book about looking AT a trans body. The transformation of the body is a huge fixation, almost a fetish, for cis folks. We just can’t seem to get that it isn’t only about changing the body. Being trans is too complicated to reduce to a single idea or experience – not matter how hard we try as cis folks to make it just about the ONE THING (*2). The intrusive gaze on Julián’s private transformation wasn’t obvious to me. Instead, a young woman pointed it out to me and in that moment I knew the truth of it.

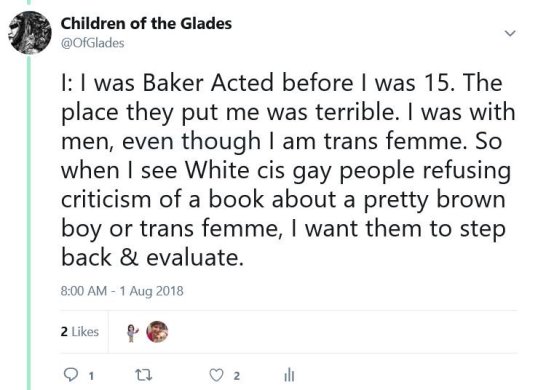

Indigo, a 16 year old trans girl (ugh, when do teens stop being boys and girls? I still call my sons’ friends boys and they are 15 and 16, so I’m going to stick with girl) who tweeted out under the Children of the Glades twitter handle dropped a truth bomb that continues to stick with me. They are a group of teens that identify as “Florida Seminole & Miccosukee” who are reading children’s and YA literature and giving scholars, teachers, librarians and other literary gatekeepers some enormous things to think about.

Indigo looked at the objectification of yet another “brown femme” body and felt danger there. Do I think that is what the author meant? No. But, it is more important to listen to what Indigo saw and felt as she read. I’d love to ask Indigo about the way she was reading this image – what gave her the creeps? Was it the heavy lidded eyes, so often associated with “bedroom eyes”? The fact that Julián is nearly naked in his tighty whities? Maybe the blush on his cheeks? When I start reading, seriously reading this image with this and some of the other commentary Indigo put out on Twitter, I began to get an inkling. I suspect the issue is the intimacy we, as outsiders, read and bear witness to seeing Julián build his gender representation from the world of his grandmother’s house.

Indigo looked at the objectification of yet another “brown femme” body and felt danger there. Do I think that is what the author meant? No. But, it is more important to listen to what Indigo saw and felt as she read. I’d love to ask Indigo about the way she was reading this image – what gave her the creeps? Was it the heavy lidded eyes, so often associated with “bedroom eyes”? The fact that Julián is nearly naked in his tighty whities? Maybe the blush on his cheeks? When I start reading, seriously reading this image with this and some of the other commentary Indigo put out on Twitter, I began to get an inkling. I suspect the issue is the intimacy we, as outsiders, read and bear witness to seeing Julián build his gender representation from the world of his grandmother’s house.

I had a lot of things I wanted to ask Indigo. She was generous in her critique, to let it out into the Twitter-verse for all to see and I feel especially lucky that I saw it, read it, reached out to her and the other Glade teens.

I have a lot of things I still want to ask Indigo about, a lot of books I want to know what she thinks of, like Alex Gino’s new You Don’t Know Everything, Jilly P. , and Rebecca Roanhorse’s Trail of Lightning. She was excited to find out that my main interest is in comics and graphic novels, so there was a whole world that was open to us to talk about … especially the new Captain Marvel movie!

But I can’t.

I can’t because she’s gone. Because, like too many queer teens and too many Native teens, and too many two spirit teens, she saw no way to survive, to move forward (Twitter announcement) . As Alexis:18 writes, “Indigo made a split-second decision that stopped her transitioning life. I know she wanted other Native 2SQ [two spirit] teens to get there.”

And so, selfishly, I mourn (*1) Indigo’s death for what I lost. Mourning for her, a teen so close to my own son’s age, feels too large and hard for me to do all at once. For her friends and family, I cannot begin to know how they feel. If I am affected by the loss of her potential, they are living with the gravity of the loss in ways I cannot know.

So, yes, Jessica Love wrote and illustrated a book that may or may not be about a young, gender fluid child, trying to find their way in the world. But, I can’t shake the feeling that this is simply not her story to write, and in the act of writing the book, she once again laid claim to what was not hers.

Rest in peace and power Indigo.

Footnotes of changes

- Updated: September 24, 2018 7:48 pm

— Added Coney Island Mermaid parade

— Tried to better explain grief. - Updated: September 24, 2018 8:08 pm

— Not surprising, I misrepresented trans experience in paragraph 5. - Updated: 9/24/18 9:57 pm — many typos.

- Updated: 9/25/18 1:38 pm — added more information about positive librarian views

Reblogged this on debraj11 and commented:

The World Is Not Changing Fast Enough To Provide Space and Safety for Every Child. I Hope This Changes That For Those Who Are Still Here.

This is a great review and a great tribute. Since the world is not changing quickly enough to provide love, acceptance, and safety for every child, it needs to change faster. We need to help it change. I think this post will help us take a step.

Thank you.

Just to clarify slightly what I said: as a practitioner, this book is vital. This is the only mainstream picture book that shows a boy dressing in a way that can to some appear as not conforming to traditional cis male gender presentation without rejection or questioning of this by other characters. This is something my patrons have explicitly asked me for, but even if they hadn’t, it would be necessary.

A book’s conception can be problematic while it’s execution can be well-done. A book can do some things well and other things not as well. Are you critiquing the book (the text and the illustrations, which give no indicator that this is or isn’t a trans character), or are you critiquing the author’s public representation of her work?

Yes. Thank you for the clarification. You are, by far, not the only professional who whole heartedly supports the book. You provide well grounded reasons for that support. Thank you.

“A book’s conception can be problematic while it’s execution can be well-done.” I’m going to have to disagree with that one. The creation of the work is directly connected to who is writing it and it shows immensely in the text and illustrations especially to anyone who has had or is having a similar experience to what the author writes about (of which she herself has no actual lived experience with). That is that non-verbal piece that is part of the book that speaks volumes to children. And unfortunately in my opinion this is not a well-done book. It is so-so and inherently problematic. The fact that is being praised the way it is speaks less to the text and illustrations being in any way good and more to the privilege attached to who is writing it and that they are telling the story in such a way that still centers and prioritizes the privileged which does not create real change.

I have the feeling that the author wrote that book as a kind of analogue to the bestselling My Princess Boy, but (apparently) just couldn’t seem to decide whether Julián should be transgender or just a queer boy.

A belated thanks for this blog post. I’ve been sending it to various people in the book industry, and so appreciate how you thoughtfully express your concerns with this book. We need so many more of these types of discussions.

Great essay. Just wanted to offer up another POV. Cis, white, 44 y.o. gay male here who wept tears of recognition at the celebration of his very own behaviors that were ignored/suppressed by adults as a child in the 80s. Seriously. Wept. I did not see a trans child. I guess some readers did. I did not see sexual orientation. I did see a Dominican boy with a loving grandmother. I did see myself. I saw myself putting on dresses in nursery school and spinning around and around like a Sufi. I saw the same captivation with feminine beauty that I had as a child. I saw the Brooklyn and Mermaid parade I know and love. I saw the subway I do not love. A child does not know who wrote the book. We do, and there’s the rub. Would love to hear Love’s take on this issue.

Great essay. Just wanted to offer up a POV. Cis, white, 44 y.o. gay male here who wept tears of recognition at the celebration of his very own behaviors that were ignored/suppressed by adults as a child in the 80s. Seriously. Wept. I did not see a trans child. I guess some readers did. I did not see sexual orientation. I did see a Dominican boy with a loving grandmother. I did see my precious little white baby-boy self. I saw myself putting on dresses in nursery school and spinning around and around like a Sufi. Okay, crying again. I saw the same captivation with feminine beauty that I had as a child being acknowledged and accepted and ENCOURAGED. I saw the Brooklyn and Mermaid Parade I know and love. I saw the subway I do not love. A child does not know who wrote the book. We do, and there’s the rub. Would Love to hear Love’s take on this issue.

Love that you identify the Mermaid Parade – maybe some back matter would have helped locate the story in a particular community experience more clearly.

I think many people read Julián as transgender because of the focus on mermaids. Transgender children often identify with mermaids. Lots of work on this subject. You can also check out Jazz Jenning’s autobiographical picture book I am Jazz.

There are VERY few own voices transgender picture books. I think that might be the closest we’ve got. Most are written by cisgender heterosexual adults.

I don’t always read Julián as trans, although I sometimes do. Today I’m reading the character through Madison Moore’s theory of fabulousness. It’s a book that invites many interpretations.

Since it’s written for kids, I wonder what kids think of it?

I wonder what kids think of it, since it’s written for kids. I’d love to see someone get the child take on it.

This is really an interesting and important take on this book. I personally love this book, and so does my daughter, because it started some good conversations. I think your criticisms and discomfort are warranted, but because this is a children’s book, things have to be simplified because of the audience it’s written for.